#78 Winter: Mild, Severe or Just Right?

What kind of weather do we hope for between November and May?

Temperatures in January of this year fell below -5 degrees Fahrenheit for several days in the Canadian grape-growing region of British Columbia. Due to this cold spell, vineyards will see an almost complete loss of fruit for the 2024 harvest season.

But the problem in British Columbia was not just the duration of the cold spell in January. It was also the unseasonably warm weather in the preceding November and December. The warmer weather meant the grapevines had not been able to acclimate to prepare for the coming cold temperatures. When the cold weather came, the vines were not ready for it.

Fortunately for us, we have Cornell University researchers who are working to understand how grapevines respond to seasonable temperature changes. Associate Professor Jason Londo studies how “cold hardiness” in grapevines changes over the range of fluctuating temperatures between late fall and early spring.

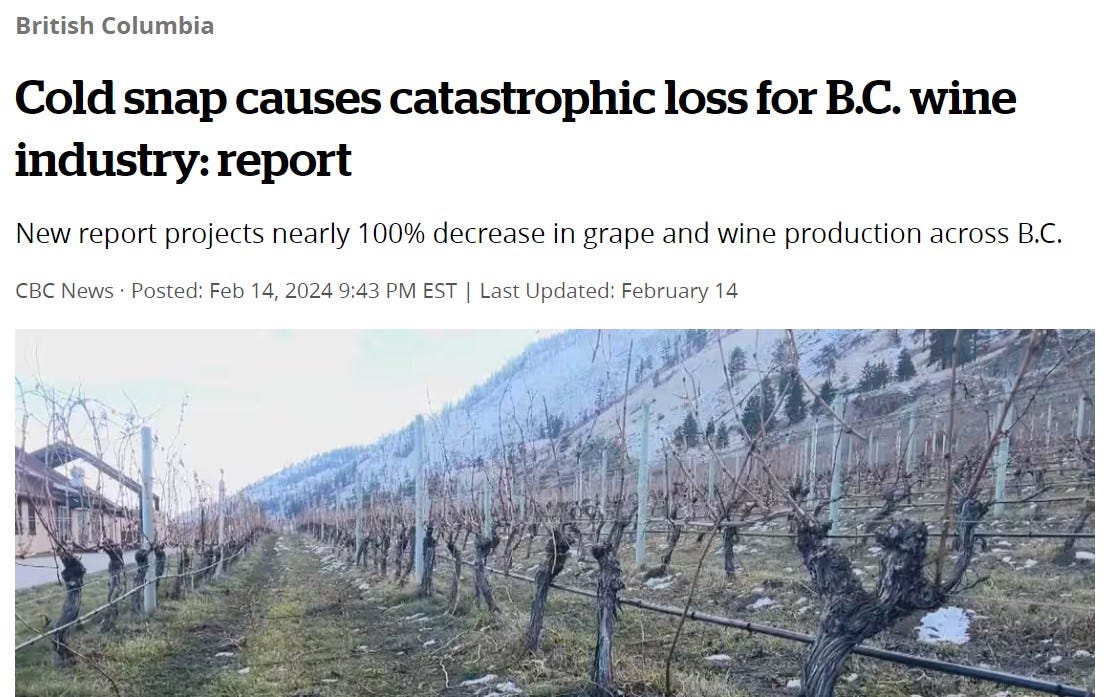

The chart below plots the way vines normally acclimate in the presence of changing temperatures. The red line in the graph is the high temperature of the period and the blue line is the low temperature.

As long as the trajectory of high and low temperatures stay within a “typical” range, vines “acclimate” to decreasing temperatures between November and January; remain dormant through late February; and then “deacclimate” from March through early May. As long as there are no extreme periods of abnormally high or low temperatures, vines will survive to produce a normal crop in the coming year.

The problem is that the changing climate seems to be disrupting this pattern. The warm weather in November and December in British Columbia is an example of this.

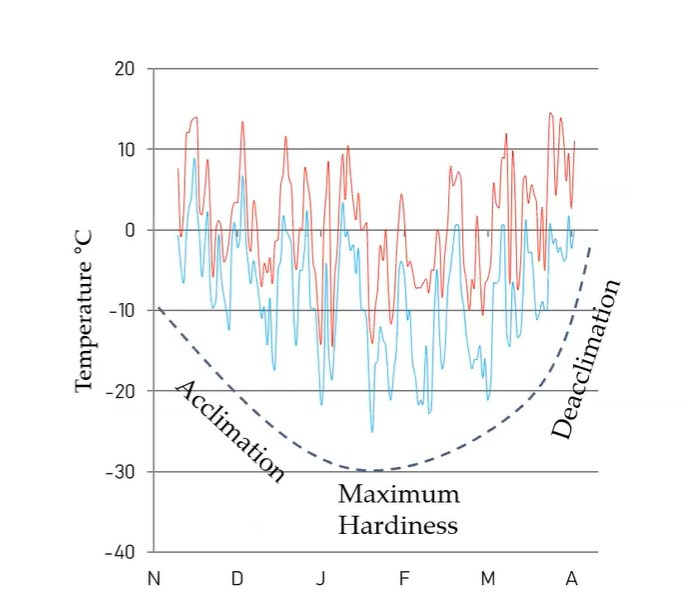

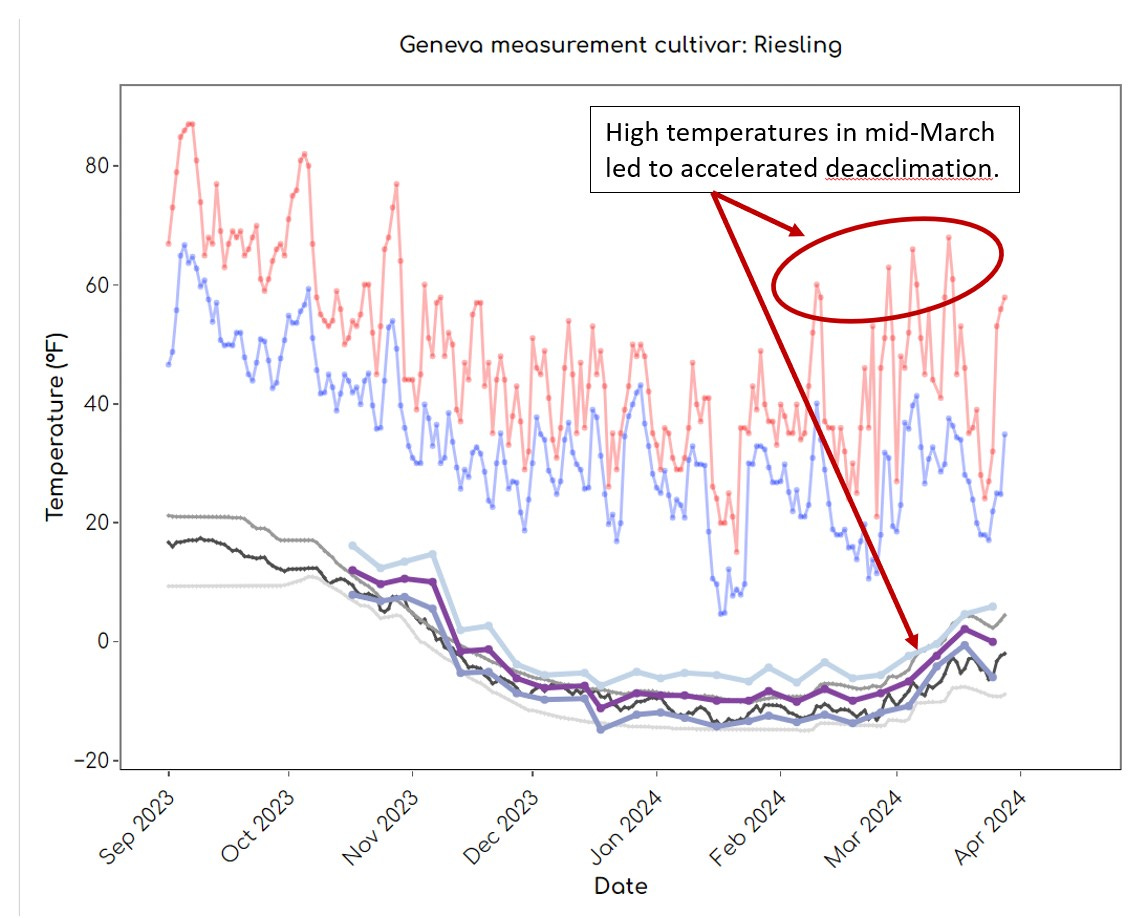

Cornell’s Londo and his team are studying how temperatures in the Finger Lakes affect the hardiness of the multiple varieties of grapes grown here. They have placed temperature sensors in vineyards around Seneca Lake (including ours), and a member of Londo’s team comes out regularly to take samples of Riesling buds to assess their hardiness. They correlate the hardiness of the buds with the temperature trends they are recording.

Londo’s team is publishing online both the temperatures and “bud hardiness” so that we can see, in real time, how “cold hardy” our vines are at any point in the growing season. They share the data so we can monitor it as it comes in.

Three weeks ago, we saw an unseasonably warm spell for three days in March. It seemed too early for temperatures that high. As Londo’s chart below shows, the deacclimation process accelerated in response to that warm weather, but when the weather became colder, the cold hardiness began to improve slightly.

Although it is important to understand the relationship between temperature and cold hardiness, the most important question is: “Is there anything we can do to improve the chances that our vines can survive these unpredictable weather patterns?”

Londo’s team (and others) are investigating various materials to spray onto the vines’ foliage just after harvest in the fall. Their goal is: to encourage the vines to acclimate at a faster rate in the fall (to avoid what happened in British Columbia); and then to slow down the de-acclimation in the spring (to avoid the effects of a late frost like the one we experienced on May of 2023).

This is a great example of a partnership between researchers and practitioners. Back in Substack #18, I addressed the conventional divide between farmer (ie, “do-ers”) and professors (ie, “thinkers”). The work of Jason Londo and his team of “thinkers” are “doing” us a great service. And it is something for us to “think” about and “do” our part to support this work.

In October of 2020, there was a very early deep freeze after a very mild fall in Western Colorado. It is an area that typically doesn’t freeze until sometime in November. Not only did they lose the 2021 crop, well over half of the vines died and had to be replaced. It was awful. Happened in the early 60’s also; totally destroyed the peach trees in Fruita.